By Meredith Mani, SDG Awareness Team Co-Chair

February is Black History Month in the US. The theme this year is Health and Wellness, which dovetails nicely with the UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) of the month, SDG #3 Good Health and Well-Being. By looking at the two together, we can see strides that have been made, but also the gaps that have increased over the last few years and the measures being taken to correct that.

The undeniable socioeconomic impact of slavery and Jim Crow are established to have led to the racial wealth gap and health disparities between African Americans and their white counterparts. Everything from redlining to denying Blacks mortgages and creating inner-city housing developments with food deserts play a role in this. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought health issues in the Black community to the forefront. Doctors and politicians fight sociocultural norms that are believed to contribute to the high rates of infection and death in the Black community. Hurdles include a historic mistrust of the medical community stemming from incidents like the Tuskegee Airmen being used as medical specimens without their knowledge to less access to health care.

The intersection between SDG #3 and the healthcare inequalities facing Black people provides a common ground for improvements. As we reflect on Black History Month and take a deep dive into the issues of systemic racism, cultural bias, inequalities and disparities, we are given an opportunity to strengthen our understanding of SDG #3 and to identify actions that will make a tangible difference.

SDG #3: Good Health and Well-Being aims to reduce or eliminate a variety of health-related problems, including:

- Maternal mortality and preventable deaths of newborns and infants;

- Communicable diseases like AIDS, COVID-19, tuberculosis and malaria, as well as deaths from disease, substance abuse and mental illness;

- Ensuring universal health coverage, including access to reproductive health services;

- Impacts of the environment through hazardous chemicals, pollution and climate change.

According to the World Economic Forum (WEF), COVID-19 has set earlier progress on health and well-being back significantly. There have been millions of deaths worldwide, and contagious variants continue to emerge and to spread. In the US, this has led to a reduction in life expectancy of 1.87 years – with further reductions in life expectancy for the Black population. With a disproportionately devastating impact on African Americans, the virus has highlighted “the structural weaknesses of not only our economic systems, but also, more critically, our health systems,” according to the WEF.

A health report by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM), a non-profit organization not affiliated with any government, suggests that the poverty African Americans disproportionately live in can’t wholly account for their shortened life spans and increased incidences of diseases like diabetes, heart attacks and obesity. NAM stated in a recent report that “racial and ethnic minorities receive lower-quality health care than white people –

even when insurance status, income, age, and severity of conditions are comparable.” NAM summarized an “uncomfortable reality” that “some people in the United States were more likely to die from cancer, heart disease, and diabetes simply because of their race or ethnicity, not just because they lack access to health care.”

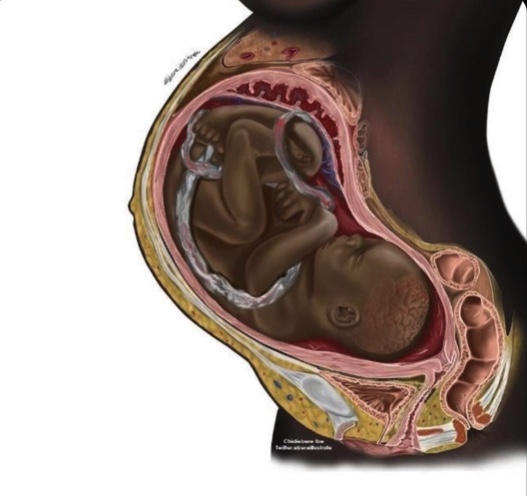

Implicit and unconscious bias in medicine is actively being addressed by the medical community. Chidiebere Ibe, a Kenyan-born medical student, recently garnered worldwide attention when his illustration of a Black fetus went viral. Ibe tells FAWCO, “This model seeks to show that Diversity, Equity, Inclusion and Respect is premised on proper representation. The long-age prejudice towards Black people in healthcare has been because people literally didn’t see themselves and couldn’t believe there was something missing. For example, when the drawing went viral it dawned on people how they never knew this was a problem eating up the system.”

Ibe goes on to say that doctors focusing on the specific needs and cultural identity of Blacks will change medicine for everyone. “These illustrations would create a better sense of belonging, give medical students who in turn would be medical doctors good and diverse materials for study, and of course change their approach towards Black people. Visual is the strongest sense and creating representative illustrations can alter people’s approach to how they see Black people and how they should value them,” Ibe stated. His approach addresses several SDGs: #3 Good Health and Well-Beng, #4 Quality Education, #10 Reduced Inequalities, #11 Sustainable Cities and Communities, and #16 Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions.

The Center for Health Journalism published an article recently that states, “Established racial disparities and discrimination have long been part of America’s health care system from birth to death. Infant mortality rates are twice as high for African Americans compared to whites. White Americans live years longer than African Americans. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) further indicates that US racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to receive even routine medical procedures and experience a lower quality of health services but that they are prioritizing ways to reduce inequalities in healthcare.”

Experts in the healthcare field have been researching this disparity intensively over the last few years. Policy makers like Dr. Steven Starks, MD believe that culturally competent care that addresses the history, array of experiences and unique sociocultural factors associated with the Black community is the best way to make inroads, because it factors in, and is empathetic to, the core values of Black culture. Starks, who is a psychiatrist, stresses the mental health component for creating lasting change in health care for the Black community.

The devastating impact of COVID-19 on the African American population is both physical and mental. Doctors like Starks, and organizations like BEAM (Black Emotional And Mental health) seek to address the mental and emotional toll left by COVID-19. Yolo Akili Robinson, the Executive Director of BEAM stated in the organization’s annual report that, “Now, as the dust has somewhat settled, we know the distress has not. Black communities were and continue to be hard hit by COVID. Grief and despair are everywhere.” When it comes to the subject of mental health, people of color are usually not a part of the conversation. There is a white-centric narrative that doesn’t depict Blacks as seeking or even needing services. Starks and BEAM think changing that narrative to include African Americans is key to having more people of color seek services. BEAM’s Mission Statement affirms that its goal is “to remove the barriers that Black people experience getting access to or staying connected with emotional healthcare and healing.”

Black women are three times more likely than white women to die in childbirth. Wealth does not seem to shift that statistic dramatically, as evidenced by the case of tennis star Serena Williams, who has won 23 Grand Slam titles. Williams nearly died after doctors failed to listen to her and her concerns after giving birth to her daughter. Blacks are also more likely to face poverty and hunger than their white counterparts.

Engaging the medical communities and local organizations to help reduce inequalities in health care is essential to achieving SDG #1 No Poverty, SDG #3 Good Health and Well-Being, SDG #4 Quality Education, and SG #11 Sustainable Cities and Communities.

Illustration used with the permission of Chidiebere Ibe.

Sources:

WebMD

The BMJ#

BEAM

CDC

The New York Times